In healthy individuals, the body regulates the oxygen-carrying capacity of red blood cells to meet physiological needs. New red blood cells are produced to replace circulating red blood cells as they reach the end of their approximately 120-day life span. Sufficient amounts of key nutrients are required to support the replacement of red blood cells at a rate of approximately 1 percent daily. Anemia results when the red blood cell oxygen-carrying capacity can no longer be maintained due to: inadequate red blood cell production; a reduction in the life span of red blood cells; increased blood loss; or a combination of these. Detecting anemia depends on identifying individuals whose circulating hemoglobin concentration is lower than the threshold used to define anemia, which varies by population groups.

Researchers have made important advances in understanding the common causes of anemia—including iron deficiency (ID), other micronutrients deficiencies, infection, inflammation, and genetic disorders:

- Iron deficiency develops if the iron circulating in the blood cannot provide the amounts required for red blood cell production and tissue needs.

- Iron deficiency anemia develops if iron-limited red blood cell production fails to maintain the circulating hemoglobin above the threshold used to define anemia.

- Absolute iron deficiency develops when reduced or absent body iron stores cannot meet an individual’s iron need. Absolute iron deficiency may be responsive to iron supplementation but is responsible for only a minority of anemia.

- Functional iron deficiency results when adequate or increased iron stores cannot meet iron requirements as a result of infection or inflammation, of complex medical disorders or of treatment with erythropoiesis stimulating agents. Functional iron deficiency is unresponsive to iron supplementation. This type of iron deficiency is frequently responsible for anemia in low- and middle-income countries and it is unresponsive to iron supplementation.

- Absolute and functional iron deficiency may coexist if circulating iron is depressed by infection or inflammation while the body’s iron stores are absent or reduced.

- Deficiencies of nutrients other than iron are much less frequent causes of anemia overall but may be important in some settings.

- Vitamin B12 and folate deficiencies interfere with red blood cell production in the bone marrow and are the next most prevalent nutritional basis for anemia.

- Generally, deficiencies of other nutrients (water soluble B-vitamins such as riboflavin, pyridoxine, and thiamine; ascorbic acid; the fat-soluble vitamins A and E; and trace elements such as copper, zinc, and selenium) are infrequent causes of anemia.

- Infection and inflammation are common causes of anemia in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Anemia may result from infection or inflammation as a result of functional iron deficiency. Some infections are also associated with suppression of red blood cell production, with increased destruction of red blood cells, increased blood loss, or combinations of these factors.

- The role of genetic conditions as causes of anemia depends upon the prevalence of specific inherited red blood cell abnormalities in the populations, geographic areas, and settings of interest.

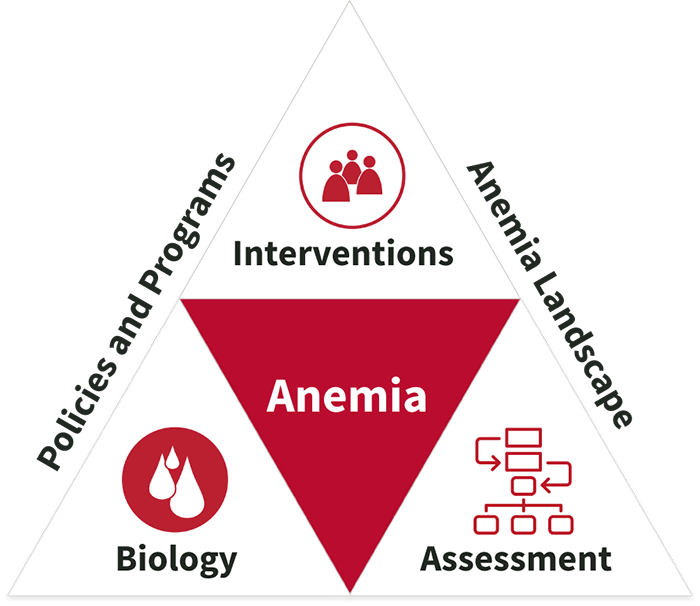

The USAID Advancing Nutrition Anemia Task force has developed five Anemia Briefs that explore current evidence and practice to understand and address the causes and consequences of anemia, and interventions to reduce the burden of disease. Three of those briefs—"The Big Five: Iron, Vitamin B12, Folate, Vitamin A, Zinc”; “Anemia and Coexisting Infection and Inflammation”; and “Anemia in Pregnancy”—explore issues related to the biological mechanisms behind the development of anemia.

We found 48 resource(s)